Vivências e Reflexões de uma mulher indígena Yepá Mahsã em terras nórdicas/Experiences and Reflections of a Yepá Mahsã Indigenous Woman in Nordic Lands

By: Patrícia Maia Yució

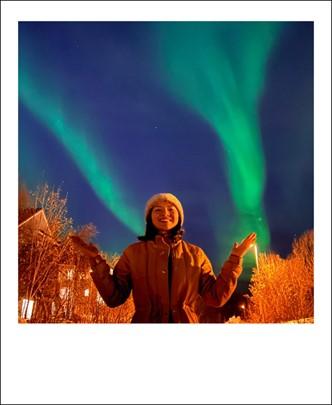

Foto 1-2: Patrícia in Tromsø

A Noruega é um sonho que habita a mente de muitos, inclusive a minha. Um sonho tecido com paisagens deslumbrantes, onde a neve abraça as montanhas e o céu se enche de cores que mais parecem retiradas de um conto de fadas. Em sua generosidade, a vida me colocou diante de duas tecelãs de sonhos: Margherita Poto e Giulia Parola. E assim, o que antes eram apenas fios dispersos em meus pensamentos, se transformou em realidade por meio do Mestrado em Direito e do projeto Eco Care.

Nasci em uma pequena comunidade indígena, chamada Cayuri, no município mais lindo do Amazonas: São Gabriel da Cachoeira, rodeada de rios, montanhas e florestas. A infância, ali, foi marcada por um profundo e silencioso contato com a natureza. Mais tarde, mudei para Manaus, uma grande capital.

Quando cheguei a Tromsø, a primeira coisa que me chamou a atenção foi o silêncio. No aeroporto, nas ruas, na universidade, a cidade parecia respirar de maneira mais tranquila. Percebi as casas sem muros, as ruas impecavelmente limpas e as águas ao redor da cidade, incrivelmente cristalinas. Foi então que constatei que existe, no mundo, uma cidade urbanizada, mas livre de poluição sonora, visual e ambiental. Foi fácil me adaptar, senti-me acolhida por esse ambiente pacífico, e uma sensação de segurança nasceu em mim. A cidade parece um cenário de filme de tão linda.

Nas ruas, vi pessoas idosas e com deficiência andando sozinhas, com naturalidade, o que é um reflexo da excelente acessibilidade da cidade. As casas intercaladas com áreas verdes e montanhas, pareciam pinturas em um quadro. Sempre encontrava alguém fazendo trilhas, correndo com seus cachorros, ou andando de bicicleta, mesmo nos dias mais gelados. A vida ao ar livre era imune ao frio, e essa convivência harmoniosa com a natureza se tornava contagiante.

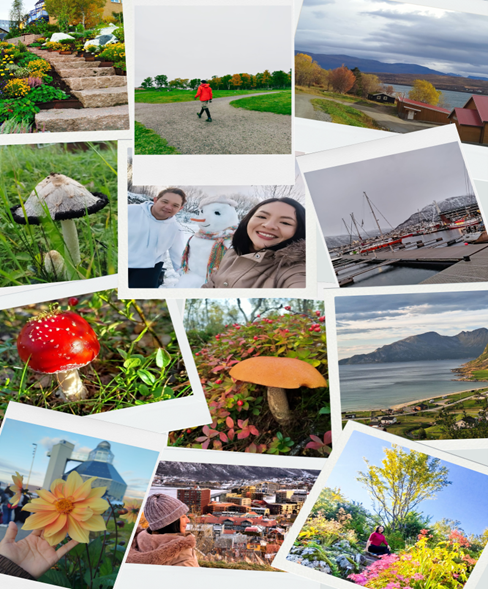

Adotei o hábito de mergulhar no mar gelado e caminhar por trilhas. As florestas, embora mais simples, encantavam pela diversidade de cogumelos, uma verdadeira explosão de formas e cores que me fascinou. Passei a sair nas horas vagas apenas para admirar esses pequenos seres da natureza. Mais tarde, descobri também um grupo de pesquisa vinculado à Universidade de Tromsø (UiT) que se reunia no Museu de Tromsø, nas tardes de domingo, para identificar cogumelos e aprender mais sobre esse reino tão encantador. Minha mente, com o tempo, passou a experimentar o estado de presença, um momento de total conexão com o que me cercava. A cada vista das montanhas cobertas de neve, das flores colorindo a cidade, ou ao observar as luzes do norte dançando nas noites, senti um bem-estar profundo. Pude ver com os meus olhos que a magia da neve é real, o frio não me incomodou, a criança que habita em mim correu pra brincar na neve.

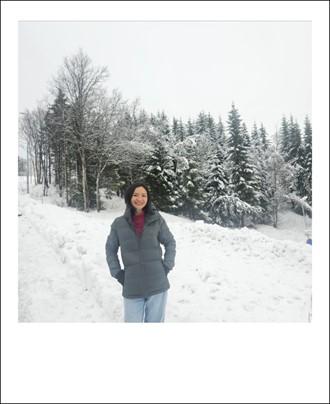

Foto 3: Caminhadas pelas trilhas, ruas e jardins de Tromsø.

Ser mulher, em muitos lugares do mundo, é viver em constante estado de adrenalina e alerta. No entanto, pela primeira vez na vida adulta, pude caminhar por uma cidade sem sentir medo. Tromsø se mostrou um lugar especialmente acolhedor para mulheres. Essa sensação de liberdade e segurança foi um dos maiores presentes que a viagem me proporcionou. Experimentei uma regeneração profunda, no corpo, na mente e no espírito.

A UiT mantém uma forte conexão com o Museu da cidade, onde percebi um grande respeito e cuidado pela história e pelos artefatos do povo Sami. Esse povo exerce um papel importante na economia local, principalmente no que diz respeito à criação de renas, atividade exclusiva dos indígenas Sami. Durante minha estadia, também aprendi que em uma cidade vizinha, onde fica o parlamento, existem estações de rádio, TV e bibliotecas que oferecem conteúdos em língua Sami. Isso demonstra um diálogo respeitoso entre os povos indígenas e o Estado norueguês, algo que me chamou muito a atenção. No Brasil, especialmente em minha cidade natal, São Gabriel da Cachoeira/AM, apesar de termos línguas indígenas co-oficiais, a presença das línguas indígenas em espaços públicos como a TV ainda é muito escassa, o que torna essa prática na Noruega ainda mais admirável.

Durante os meus estudos na Universidade de Tromsø, tive a oportunidade de participar de debates interessantes. Uma das discussões que mais me tocou foi sobre a descolonização da pesquisa no mestrado. A proposta da disciplina nos convidava a repensar a ciência, buscando novas formas de entender o mundo e o conhecimento a partir da visão indígena. Essa reflexão, que já havia começado para mim na disciplina de Antropologia com o professor João Paulo Barreto, na Universidade Federal do Amazonas (UFAM), agora se ampliava, ganhando novas perspectivas.

Uma das surpresas mais enriquecedoras foi a presença de um professor indígena Sami, que lecionava a disciplina de Direitos dos Povos Indígenas. Essa experiência foi única, pois, no Brasil, infelizmente, ainda não encontramos essa representação indígena no ensino do Direito, ao menos no Amazonas.

Foto 4: Aula com o professor Ande Somby

Foto 5: Minha apresentação na Disciplina

Foto 6: Encontro no Museu de Tromsø de Introdução aos Estudos Indígenas

Embora a barreira do idioma tenha sido um desafio nas atividades acadêmicas, ela não afetou meu dia a dia de forma significativa. As aulas sobre questões indígenas reforçaram a importância da minha presença naquele espaço, além de evidenciar a necessidade de mais indígenas nesses ambientes. O inglês e outros idiomas ainda são privilégios de determinadas classes sociais em meu estado, mas, felizmente, as professoras do Eco Care levaram outros fatores em consideração na seleção, como a legitimidade da causa ambiental e indígena.

Estar em uma terra estrangeira, com todas as minhas necessidades básicas atendidas, finalmente me proporcionou o tempo necessário para aprender um novo idioma. Apesar do curto período de dois meses, senti uma grande evolução na compreensão do idioma. O melhor modo de aprender, sem dúvida, é por meio da prática, e essa experiência foi muito enriquecedora nesse aspecto também.

Esse intercâmbio me proporcionou uma reflexão profunda sobre a sociedade em que vivo. Pude observar, com mais nitidez, o quanto o Brasil é imensamente rico e diverso em belezas naturais e culturais, especialmente na Amazônia. No entanto, também percebi o grande contraste na qualidade de vida, no cuidado com as nossas águas e na ausência de um contato mais íntimo com a natureza nas cidades mais urbanizadas, como Manaus. Sou de comunidade indígena; cresci entre pessoas agarradas à terra. Minha família é de cultivadores de mandioca e de frutas nativas. A floresta foi a minha primeira professora. Sou verdadeiramente feliz dentro dela e nadando no rio negro. Mas, na capital, esse vínculo cotidiano não existe. Não é acessível. E isso me faz perguntar: como as pessoas podem desenvolver amor e cuidado por algo que elas não conhecem e não possuem memória afetiva?

Em Tromsø percebi que desde cedo as crianças têm a natureza como parte do seu cotidiano, muitas vezes vi fileiras de crianças saindo com monitores para fazer trilhas ali perto da escola, por exemplo. Foi fácil me adaptar à cidade, pois estava com um povo parecido com os ribeirinhos com quem fui criada, os noruegueses também são agarrados à terra em que vivem, cuidam porque amam.

Sou uma mulher indígena do povo Yepá Mahsã, mãe, advogada e pesquisadora. Eu gostaria de poder ser apenas uma mulher indígena em meu território, cultivando minha roça, fazendo vinhos de pupunha e açaí, e acompanhando minha filha crescer livre, em contato pleno com a natureza. No entanto, as violências institucionais me obrigaram a buscar uma educação formal para não ser ainda mais massacrada por este mundo. Hoje pesquiso sobre o acesso à justiça para mulheres indígenas, porque sei que, quando elas estão bem em suas terras, conseguem nutrir suas famílias e também a sociedade como um todo. A mulher indígena tem uma ligação direta com a proteção dos territórios, e os territórios indígenas são, hoje, uma das chaves centrais para enfrentar os impactos das mudanças climáticas.

Por fim, Tromsø se revelou uma cidade charmosa, segura, vibrante e repleta de belezas naturais. Fui acolhida por sua terra e banhada pelas águas puras. O maior desejo que levo comigo é que todos possam viver em seus próprios países com a mesma qualidade de vida e em harmonia com a natureza. A experiência de intercâmbio foi muito mais do que eu esperava: além do aprendizado acadêmico, foi um grande aprimoramento pessoal. A maior lição que trago de Tromsø foi sobre o amor, manifestado no cuidado, afeto e bem-estar, elementos fundamentais para uma vida plena e equilibrada com o meio ambiente.

***

Norway is a dream that inhabits the minds of many, including mine. A dream woven with breathtaking landscapes, where snow embraces the mountains and the sky is filled with colors that seem straight out of a fairy tale. In its generosity, life has placed me before two dream weavers Margherita Poto and Giulia Parola. And so, what were once just scattered threads in my thoughts, became reality through the Master's degree in Law and the Eco Care project.

I was born in a small indigenous community called Cayuri, in the most beautiful municipality in Amazonas: São Gabriel da Cachoeira, surrounded by rivers, mountains, and forests. My childhood there was marked by a deep and silent connection with nature. Later, I moved to Manaus, a large capital city.

When I arrived in Tromsø, the first thing that struck me was the silence. At the airport, in the streets, at the university, the city seemed to breathe more calmly. I noticed the houses without walls, the impeccably clean streets, and the incredibly crystal-clear waters surrounding the city. It was then that I realized that there is, in the world, an urbanized city, but free from noise, visual, and environmental pollution. It was easy to adapt; I felt welcomed by this peaceful environment, and a sense of security was born within me. The city looks like a movie set, it's so beautiful.

On the streets, I saw elderly people and people with disabilities walking alone, naturally, which reflects the city's excellent accessibility. The houses, interspersed with green areas and mountains, looked like paintings on a canvas. I always found someone hiking, running with their dogs, or cycling, even on the coldest days. Outdoor life was immune to the cold, and this harmonious coexistence with nature became contagious.

I adopted the habit of diving into the icy sea and hiking along trails. The forests, though simpler, enchanted me with their diversity of mushrooms, a true explosion of shapes and colors that fascinated me. I started going out in my free time just to admire these little creatures of nature. Later, I also discovered a research group linked to the University of Tromsø (UiT) that met at the Tromsø Museum on Sunday afternoons to identify mushrooms and learn more about this enchanting kingdom. Over time, my mind began to experience a state of presence, a moment of total connection with my surroundings. With each view of the snow-covered mountains, the flowers coloring the city, or watching the northern lights dancing in the nights, I felt a profound well-being. I could see with my own eyes that the magic of snow is real, the cold didn't bother me, the child within me ran to play in the snow.

Being a woman, in many parts of the world, means living in a constant state of adrenaline and alertness. However, for the first time in my adult life, I was able to walk through a city without feeling afraid. Tromsø proved to be an especially welcoming place for women. This feeling of freedom and security was one of the greatest gifts the trip gave me. I experienced a profound regeneration, in body, mind, and spirit.

UiT maintains a strong connection with the city's museum, where I noticed great respect and care for the history and artifacts of the Sami people. This people plays an important role in the local economy, especially regarding reindeer herding, an activity exclusive to the Sami indigenous people. During my stay, I also learned that in a neighboring city, where the parliament is located, there are radio and TV stations and libraries that offer content in the Sami language. This demonstrates a respectful dialogue between indigenous peoples and the Norwegian state, something that greatly impressed me. In Brazil, especially in my hometown, São Gabriel da Cachoeira/AM, despite having co-official indigenous languages, the presence of indigenous languages in public spaces such as television is still very scarce, which makes this practice in Norway even more admirable.

During my studies at the University of Tromsø, I had the opportunity to participate in interesting debates. One of the discussions that touched me the most was about the decolonization of research in the master's program. The course proposal invited us to rethink science, seeking new ways of understanding the world and knowledge from an indigenous perspective. This reflection, which had already begun for me in the Anthropology course with Professor João Paulo Barreto at the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), was now expanding, gaining new perspectives.

One of the most enriching surprises was the presence of an indigenous Sami professor, who taught the subject of Indigenous Peoples' Rights. This experience was unique because, unfortunately, in Brazil, we still do not find this indigenous representation in legal education, at least not in Amazonas.

Although the language barrier was a challenge in academic activities, it did not significantly affect my daily life. The classes on indigenous issues reinforced the importance of my presence in that space, in addition to highlighting the need for more indigenous people in these environments. English and other languages are still privileges of certain social classes in my state, but fortunately, the Eco Care professors took other factors into consideration in the selection process, such as the legitimacy of the environmental and indigenous cause.

Being in a foreign land, with all my basic needs met, finally gave me the time I needed to learn a new language. Despite the short period of two months, I felt a great improvement in my understanding of the language. The best way to learn, without a doubt, is through practice, and this experience was very enriching in that aspect as well.

This exchange provided me with a profound reflection on the society in which I live. I was able to observe, with greater clarity, how immensely rich and diverse Brazil is in natural and cultural beauty, especially in the Amazon. However, I also perceived the great contrast in quality of life, in the care for our waters, and in the absence of a more intimate contact with nature in more urbanized cities, such as Manaus. I am from an indigenous community; I grew up among people clinging to the land. My family are cassava and native fruit growers. The forest was my first teacher. I am truly happy within it and swimming in the Rio Negro. But, in the capital, this daily connection does not exist. It is not accessible. And this makes me wonder: how can people develop love and care for something they do not know and have no emotional memory of?

In Tromsø, I realized that from a young age, children have nature as part of their daily lives. I often saw lines of children leaving with monitors to go hiking near the school, for example. It was easy for me to adapt to the city because I was with people similar to the river dwellers I grew up with; Norwegians are also very attached to the land they live on, they take care of it because they love it.

I am an Indigenous woman from the Yepá Mahsã people, a mother, lawyer, and researcher. I wish I could simply be an Indigenous woman in my territory, cultivating my fields, making wine from pupunha and açaí, and watching my daughter grow up free, in full contact with nature. However, institutional violence forced me to seek formal education to avoid further oppression by this world. Today, I research access to justice for Indigenous women because I know that when they are well on their lands, they can nourish their families and society as a whole. Indigenous women have a direct connection to the protection of territories, and Indigenous territories are, today, one of the central keys to facing the impacts of climate change.

Finally, Tromsø revealed itself to be a charming, safe, vibrant city full of natural beauty. I was welcomed by its land and bathed by its pure waters. My greatest wish is that everyone can live in their own countries with the same quality of life and in harmony with nature. The exchange experience was much more than I expected: in addition to academic learning, it was a great personal growth. The greatest lesson I take from Tromsø was about love, manifested in care, affection, and well-being, fundamental elements for a full and balanced life with the environment.

Foto 7: em Sommarøy, uma ilha linda, acessível por transporte público.

***

This blogpost can be cited as: Patrícia Maia Yució, Vivências e Reflexões de uma mulher indígena Yepá Mahsã em terras nórdicas/Experiences and Reflections of a Yepá Mahsã Indigenous Woman in Nordic Lands, December 8, 2025.