Ocean Eyes: a project between law, environment and multi-sensoriality

By: Federica Vincenti

The "Ocean Eyes" project was developed by a group of four students from the University of Turin-Stefano Casaburo, Luigi Mello, Edoardo Marino, and Federica Vincenti-as part of the Environmental Law course of the Faculty of Georisorse and Ecosustainable Business Management, with the aim of devising a critical and creative reflection, supported by legal analysis, on ocean and coastal risks and the related resilience of local communities, particularly the Māori community.

The project is developed within the normative context of the 2030 Agency for Sustainable Development, with particular reference to SDG

14 - Life Underwater, and proposes art as a communicative language. It translates into the creation of a poster and playbill depicting symbols and broader cultural references related to ocean pollution and the indigenous Māori community, with the intention of creating a visual experience that can make people think and move. To make the experience multisensory, there is a QR code containing an evocative sound track related to Māori culture, entitled "Ororuarangi."

Agenda 2030, Oceans and Environmental Justice

The 2030 Agenda was adopted in 2015 by the 193 member states of the United Nations. It does not constitute a binding treaty, but rather a political and moral commitment to transform the world through 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which range from combating poverty to mitigating climate change, but are found to be closely interconnected.

A cardinal principle of the Agenda is that no one should be left behind.

The project we are presenting stems from a specific reflection on Goal 14 - Life Under Water, which calls us to sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources to foster the most balanced development possible. We often tend to underestimate the importance of the oceans, just think of the fact that about 75% of the Earth's surface is made up of oceans, which contain almost all of the planet's water resources.

In addition, oceans play an important role in climate change mitigation, as they regulate the atmospheric system; they provide habitats for some 200.000 species, whose biodiversity is critical to the maintenance of ecosystem services; and they are a primary food security resource, providing sustenance for more than three billion people.

How can this translate into concrete action?

The Aarhus Convention, signed in 1998 and entered into force in 2001 in the member states of the European Union, is a legally binding instrument that guarantees three important rights in environmental matters: access to information, participation in decision-making processes, and access to justice.

Article 4 of the Convention grants any natural or legal person the right to request environmental information from the competent public authorities, without having to justify the request. Such information must be provided within 30 days of submitting the request.

What if the information is not available? The public authority is obliged to indicate who holds it.

Is this always possible? Except in some cases, such as for reasons of national security or when the information is still being prepared.

In the same way, Article 6 guarantees participation in environmental decisions and in the development of projects or regulatory instruments concerning the environment. Participation must occur in the early stages of the process, where the public must be informed about the subject of the decision, the environmental assessment, and the decision-making procedure.

Article 9 establishes the third pillar of the Convention: access to justice in environmental matters. In which cases? When the right to access information is not respected, the right to participate in environmental decisions is violated, or national environmental law is breached.

Two works, one message

The project consists of two separate but connected graphic productions: an initial playbill and a final poster. Both have a symbolic language, inspired by the culture of the indigenous Māori community, with the intention of capturing the viewer's visual curiosity and developing a reflection to discover the ocean and the environmental and social injustices behind it.

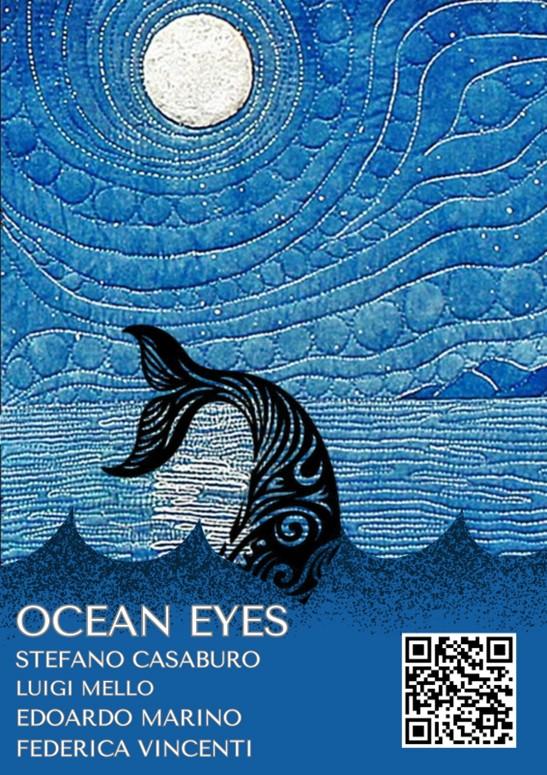

Figure 1: The Project Cover

The poster introduces the project through an evocative image: a whale tail stylized according to the ornamental motifs of the Māori culture, emerging from the ocean on a deep night. In addition, there is a QR code at the bottom to create a bridge between aesthetics and knowledge: it leads back to some info about us, the creators of the project, and an explanation about the meaning of it.

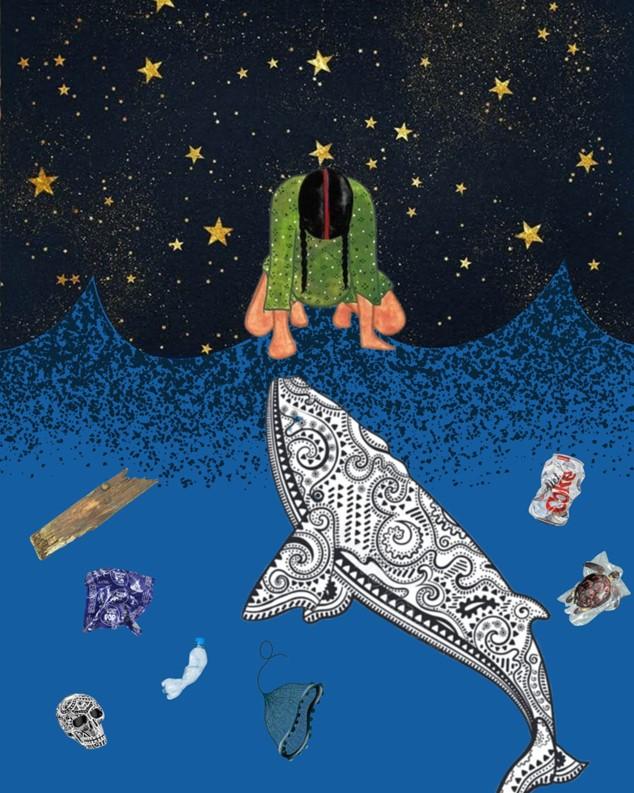

The final poster is designed to be displayed in public spaces and directly addresses the public. In the foreground is a whale, a symbol of ocean ecosystems and the negative effects of marine pollution, stylized with decorative motifs that are inspired by Māori culture, such as intertwined lines, spirals, and elements that express the connection with nature. Above the whale is an indigenous figure to represent the Māori Community, whose connection with nature is now at risk of marginalization and silencing.

In the background we find several interconnected symbols, which refer to different imaginaries:

-a wood fragment represents the felling of sacred trees;

-the skull represents the concept of balance between life and death and the cultural marginalization of the Māori community from environmental decision-making processes;

-the turtle trapped in plastic and the plastic bottle broadly represent pollution;

-the Coca-Cola can and the fishing net symbolize the Western claim to supremacy and the colonization policies that have impacted indigenous peoples.

Ororuarangi: echo of the sky in our project

The Ocean Eyes project does not limit itself to the visual dimension but seeks to create multisensoriality and greater inclusivity through a sound component—one that goes beyond merely being auditory and instead amplifies the visual meaning of the poster.

Ororuarangi is a track that struck us for the emotions and meanings we wanted to convey.

In Māori culture, the word rangi means “sky,” while ororua is not a commonly used term to indicate “echo.”

However, within the overall imagination of the project, we envisioned Ororuarangi as evoking the idea of a sound that disperses through the air and aligns with Māori spirituality—a culture that transcends the purely analytical.

The song was released in 2021 by the collective IA, composed of Reti Hadley, Moetu Smith, and Turoa Pohatu. Its roots lie in taonga pūoro, the ensemble of traditional Māori musical instruments, with particular attention to the pūtōrino, a flute whose shape is inspired by the larva of the moth and which holds a deep connection to the goddess of music, Hineraukatauri, in Māori mythology.

An electronic drum accompaniment played by a member of the group was added to the track. The process was simple: the vocal part of the track was initially isolated using software, then the drum track was recorded, and finally, the two parts were combined using a smartphone.

To fully respect the track, we decided to contact its creators via Instagram, and they kindly granted us their permission.

In our project, music does not play a secondary role but serves as a true narrative voice that accompanies, amplifies, and in some cases even replaces visual reflection.

Figure 2: The final project

Reflections on the display of the Ocean Eyes poster at the Comala Cultural Center

We decided to exhibit the final poster at the Comala Cultural Center in Turin, which we consider an important space for community engagement and raising awareness on social issues such as environmental sustainability.

It was very interesting to observe the audience’s diverse reactions, which offered us further insights and reflections.

How so?

Some viewers perceived a sense of sadness and vulnerability, almost as if the poster were a silent cry about the fragility of ocean ecosystems, pollution, and the marginalization of Indigenous communities.

Others interpreted it in a more positive light, sensing a message of hope—as if the figure of the Indigenous person symbolized a reclaiming of the bond with nature, not entirely lost, and a form of resilience.

In a few residual cases, the reaction was one of indifference, which we generally interpreted as a lack of information on the subject and, unfortunately at times, a lack of interest.

The experience went beyond the visual and became more evocative when viewers scanned the QR code on the poster, which linked to the Ororuarangi audio track, creating a bridge between image and sound.

At the same time, we chose to distribute smaller versions of the original poster to provide a more detailed explanation of ourselves and our project, thus broadening audience engagement.

Ocean Eyes began as an academic project, but right from the start it stimulated critical thinking in us with respect to such an important issue, reinterpreting it in a creative and multisensory way, allowing us to have confirmation that art has an important communicative and awareness-raising role.

***

This blogpost can be cited as: Federica Vincenti, Ocean Eyes: a project between law, environment and multi-sensoriality, May 14, 2025.