Indigenous Communities Face Challenges Amid Nutrition Transition

Indigenous communities across the Arctic are grappling with the profound effects of the global nutrition transition, a shift from traditional diets to modern, processed foods.

This transformation, driven by urbanization, globalization, and economic pressures, is not only altering food habits but also threatening cultural traditions, health, and sustainability.

The nutrition transition, as explained by Ingvild Jensen, an Assistant Professor at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, is part of a broader epidemiological shift.

“In the last 30 to 40 years, we’ve seen a change in the disease panorama. We’ve moved from infectious diseases to chronic conditions like obesity and diabetes, which are now major global health challenges,” Jensen said.

The Loss of Traditional Diets

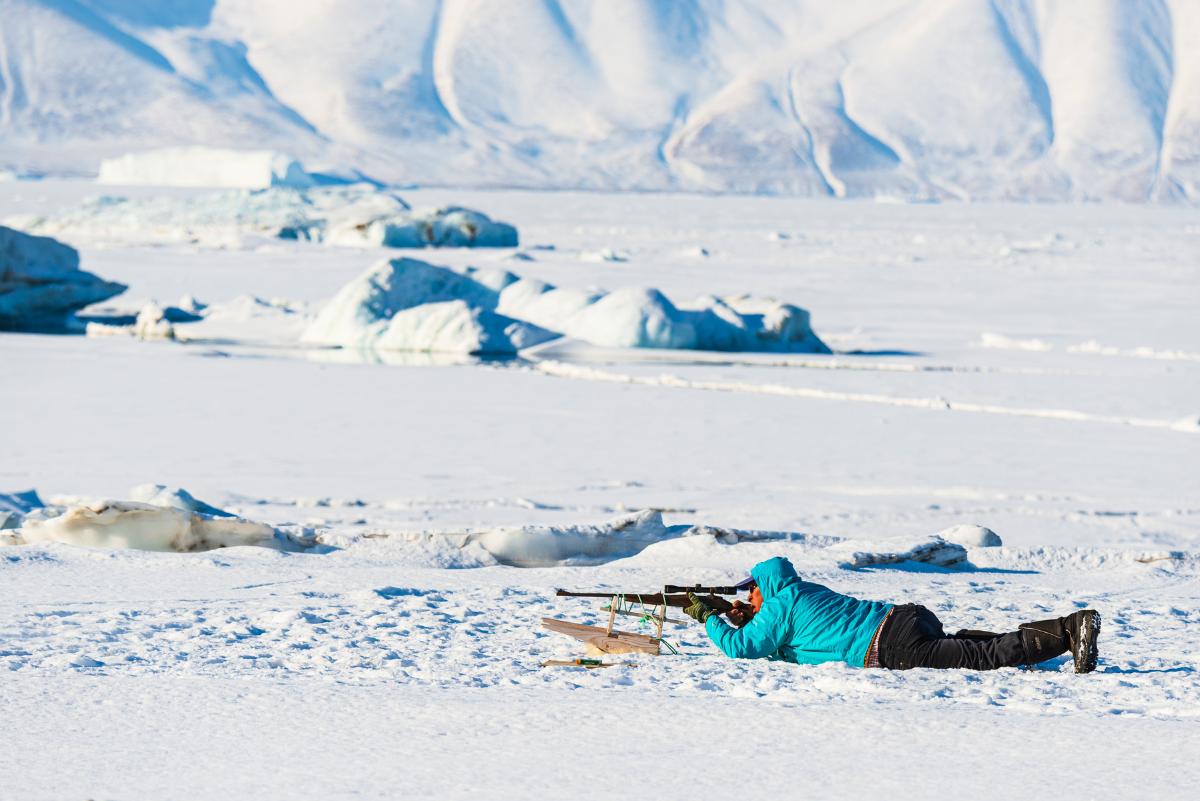

For Indigenous peoples, the transition has been particularly disruptive. Traditional diets, rich in locally sourced foods like fish, seal, whale, and caribou, are being replaced by store-bought, processed goods. This shift has led to a decline in essential nutrients and an increase in health issues.

“The Indigenous people have survived for thousands of years because they knew what to eat and how to get the vitamins and minerals they needed,” Jensen noted.

“But now, traditional foods are being lost, and with them, the knowledge that sustained these communities.”

Norja Walther, a student from Germany, who lives in Nuuk and is studying at Ilisimatusarfik, the University of Greenland, highlighted the role of colonialism in this dietary shift.

“In Greenland, for example, the Danish government promotes milk in schools, even though over half of the Inuit are lactose intolerant. Instead of encouraging traditional sources of calcium, like dried fish, imported goods are prioritized,” Walther said.

“This is colonialism changing the diet.”

Health Impacts and Cultural Disruption

The introduction of processed foods has led to rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses among Indigenous populations. Jensen pointed out that one can be overweight and still malnourished. You might get enough energy, but not the vitamins and minerals your body needs.

Beyond physical health, the nutrition transition is also affecting mental well-being and social cohesion.

“Hunting and gathering aren’t just about food—they’re about spending time with family, being in nature, and maintaining cultural traditions,” Walther explained.

“When those practices are lost, it disrupts social bonds and can lead to mental health problems.”

The challenges are compounded by environmental issues. Pollution and climate change are making traditional food sources less reliable.

“Heavy metals in the blubber of marine animals and overfishing by large corporations are reducing the availability and safety of traditional foods. This forces communities to rely on expensive, low-quality imported goods,” said Walther.

Economic and Political Pressures

Economic factors also play a significant role. Rising incomes and urbanization have led to changes in food preferences, while the high cost of importing fresh produce to remote Arctic regions limits access to healthy options.

“In Nuuk fresh vegetables are extremely expensive. In East Greenland, where ships only come half the year, most food is frozen and processed,” said Walther.

Jensen emphasized the political dimensions of nutrition.

“Food is deeply tied to politics,” she said.

“Governments can influence diets through taxes on unhealthy foods, subsidies for fruits and vegetables, and education programs. But they must also respect Indigenous food sovereignty—allowing communities to decide what they want to eat and how to sustain their traditional food systems.”

The Way Forward

“It’s not just about food security—it’s about food sovereignty,” Walther argued.

“We need to make traditional foods safe and accessible, rather than focusing on importing goods like lettuce or pineapples to the Arctic.”

Others highlighted the need for better conservation policies.

“Marine protected areas and bans on hunting often ignore the needs of Indigenous communities,” Soraya Grigoriou Gratton, a master’s student from France studying at UiT, said.

“These decisions are made by centralized governments without consulting the people who live there.”

Jensen concluded the session by stressing the importance of preserving traditional knowledge:

“If we lose the skills of hunting, fishing, and gathering, we lose a vital part of Indigenous culture. It’s crucial to teach younger generations how to sustain these practices, even in the face of modern challenges.”